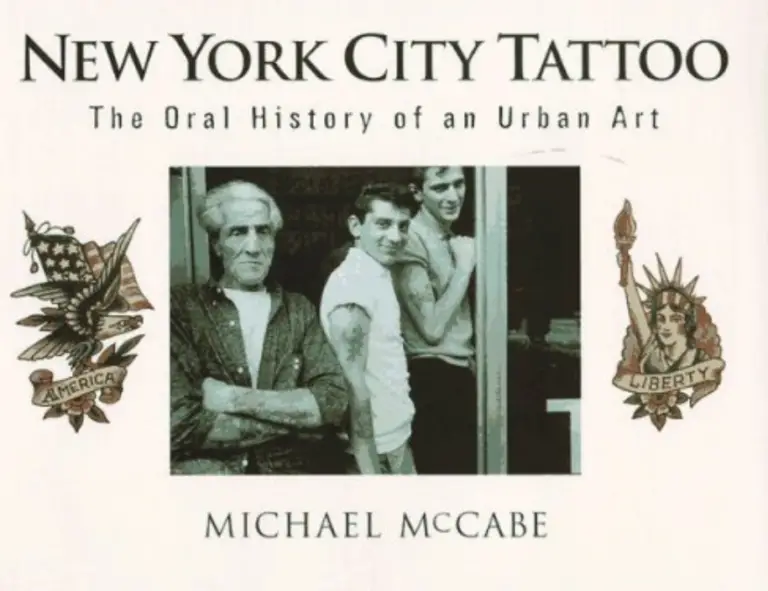

New York City Tattoo, long known for its direct, straight-forward style expressing sentiments of loyalty and love, had its origins in an area where the pre-Civil War Bowery (which was called “The Thief’s Highway”) terminated on the southern end of the island of Manhattan. This area was known as Chatham Square. Deep-water sailors as well as street-bred rough and tumblers frequented what soon became the most widely recognized and respected tattoo center in the world. (Photo Left: Stanly Moscowitz recieves the lifetime achievement “Love Thy Neighbor” Award at Crazy Philidelphia Eddie’s Body Art Festival 1999.)

Long before Samuel O’Reilly set up shop in Chatham Square with his “Electric Engraving Pen”, tattooing had a distinct presence in New York. Any sailor at the time who wandered a few blocks down South Street from the docks would have found himself in the middle of a run-down, overcrowded tenement area where the population often exceeded 15,000 people per square mile. These were rough streets controlled by the likes of Patsy Conroy and the Daybreak Boys. If the same sailor made it back to his ship with his teeth and purse intact, he thought himself lucky.

The center of this world was Chatham Square. People congregated there, among the flophouses, gin mills, dime museums and burlesque theaters, looking for entertainment. Sailors caroused away their shore leave in the beer halls and cathouses there. Confidence men and “cut purses” fleeced inexperienced seamen, many of whom drowned their sorrows in the bitter-sweet smoke of the opium dens along Doyers and Pell Streets.

There were a lot of tattoos. Everything from personal amulets to gang markings and protective charms, but especially patriotic Columbias proclaiming allegiance to the nation. New York City police inspector Thomas Byrnes reported in the mid-19th century that most of the downtown underworld characters sported extensive hand-done tattoos.

(Photo left-right: Lyle Tuttle, Walter Moscowitz, Stanley Moscowitz, Don Ed Hardy, Eddie Funk.) Most tattooers of the day were transient and the art was unorganized. Before tattoo machines, most people either tattooed themselves or had it done by friends or cohorts. Sailors passed the long hours aboard ship “pricking” designs into their own skin or that of their mates. The designs were a mix of patriotic and protective images and it was common practice to mix gunpowder into the ink, thinking it possessed magical powers of longevity. The seamen of that day were the most experienced with tattoos because they traveled so extensively. They saw the dragons of the China Station, the Christian charms of the Mediterranean and the highly detailed designs of Edo and Yokohama. Sailors bearing these exotic designs, passed through the port of New York everyday, greatly influencing and broadening the very concept of “tattoo” itself.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, thousands of men from New York, too poor to buy their way out of the draft were conscripted into the Union Army. Thousands of these same men were tattooed on the battlefields. Martin Hildebrandt, one of the first American tattooers of record, was a migrant battlefield tattooer. Being indifferent to politics, he ran back and forth from the Confederate and Union sides, setting up shop wherever the trade was best.

The demand for patriotic designs grew tremendously during that war. Tattoos of major battles, complete with the locations of key exchanges, were very popular. Like the orldly mariners of the time, tattooed soldiers returning home from the battlefields made an impression on the tattoo scene in New York City.

Tattooing was revolutionized by Samuel O’Reilly’s invention of the electric tattoo machine during the last decade of the 19th century. The time required to complete a design went from hours to minutes, moving the art away from personally conceived, hand picked designs towards established flash with its distinctly different feel.

The years ahead would see vast improvements in O’Reilly’s machine, plus the establishment of numerous tattoo equipment manufacturing companies, which worked to standardize the industry.

During the time that O’Reilly was setting up shop in Chatham Square, legions of new recruits were shipping out for battle in the Spanish-American War. His machine made the art fast and profitable. As a result he was flooded with business, often grossing over $100.00 a day, a fortune in the 1890′s in America. It wasn’t long before a host of people started getting into the act.

During the first decade of the 20th century, a percentage of the transient tattooers who had been traveling around the United States began to settle down. Many of them came to New York, which had always been a tattoo town. For years, “canvasbacks” had been displayed in the dime museums along the Bowery.

The usual set-up for a tattooer at the time was to rent a space in the back of a barber shop, putting the flash in the window up front. With a war on, New York was full of ships and sailors. The fast, colorful tattoo work of the town soon became the favorite of the fleets, setting a standard for the rest of the world.

Tattooing really took off in New York City with the 20th century. The invention of the tattoo machine that halved the time and allowed for radically different work, back to back wars, and a tattoo fashion fad initiated by the “Uptown Aristocracy” all combined to keep the tattooers of Chatham Square very busy.

Then as now, every artist attempted to separate himself from the crowd with specialties ranging from the pragmatic to the eccentric. One tattooer who elevated himself above the rest was Charlie Wagner, a former waterfront watchman who became O’Reilly’s apprentice. Wagner gave himself the title of “Professor”, and after O’Reilly’s death in 1908, became recognized as the premier tattoo artist in New York City.

At the time, all the competing artists boasted of cheaper prices, novel designs, better colors or secret removal techniques, the more bizarre of which called for the use of mother’s milk. As a side-line, Chatham Square tattooers called themselves “Black Eye Specialists” and cosmetically corrected blackened eyes with a smear of white ink. For a while tattooers were imported from exotic Japan.

Wagner was able to climb to the top of this heap, partly because of his gift of gab, and partly because of the exposure he received by tattooing a few celebrities of the time such as famous side-show performer May Artoria among others.

Refusing to use stencils, Wagner only worked freehand. He considered the majority of his competition to be mere “jaggers”, and may have been correct in his thinking. For while names like Adam Ogent, Joe Vanhart, Lew Alberts and Millie Hull stand out, no one achieved Wagner’s fame or notoriety.

The expansion of popular culture in America that accompanied the cultural growth of the 20th century had a dramatic influence on tattooing. Long a religious country, America had also been at war four times in just 56 years and the combined influence worked to keep both patriotic and religious flash a popular request.

Life in the first few decades of the 20th century saw the development of new standards people used to define themselves. These new notions of “self” extended far beyond the traditional boundaries of “God and Country”. In order to keep pace with this new complexity, tattooing had to change and adapt, and it did.

New York tattooers became very adaptable. They had to be. Changing styles and trends hit New York long before the rest of the country. New flash developed reflecting the tempo of the times: comic strip characters like Mickey Mouse and Felix the Cat, Lindbergh’s crossing, stars and starlets of the silver screen and phrases that were popularized in the press all worked their way into the changing vocabulary. Cosmetic tattooing had its origins during this time period, with many artists offering specialties such as moles and beauty marks, rosy cheeks and red lips. As a result, tattooers in Chatham Square stayed busy right up until the Crash of ’29.

With the Depression, everything began to die. Merchant shipping started to dry up and with the U.S. Navy in the Pacific, it wasn’t long before Chatham Square saw breadlines instead of lines of customers eagerly waiting for a tattoo. The beer halls and burlesque theaters that had catered to the tattooing crowd began to close up. Many tattooers packed it in and moved on. Those who stayed dropped their prices considerably. The forecast was gloomy.

It took the Second World War to revitalize the trade, although it never returned to its former glory. By this time most of the trade had moved to Coney Island where a few tattooers from the Bowery had summered through the years. With the extension of the subway system in the ’20′s, Coney Island blossomed into a playground of popular entertainment known the world over. Each summer saw millions of people escaping the steaming streets of Manhattan and Brooklyn for only a nickel subway ride.

Coney Island and then the Madison Square Garden district soon became the new centers of tattoo in New York City. A section near the boardwalk in Coney Island even earned the nickname “Tattoo Alley” where well known artists like Brooklyn Blackie worked on servicemen and civilians alike.

The rowdy days of the Thief’s Highway were gone for good. Chatham Square was changing into Chinatown and various reform groups were trying to clean up the Lower East Side. Only a few memories were left in the tattoos of the old men milling around and chatting in the barber shops and newsstands.

0 Comments